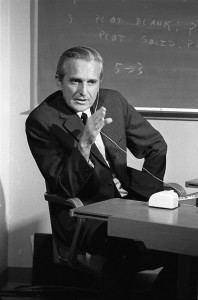

MENLO PARK, Calif.—July 3, 2013—Computing visionary Douglas C. Engelbart, Ph.D, passed away peacefully at his home in Atherton, California on July 2, 2013. He was 88 years old. Engelbart’s work is the very foundation of personal computing and the Internet. His vision was to solve humanity’s most important problems by using computers to improve communication and collaboration. He was world famous for his invention of the computer mouse and the origins of interactive computing. — SRI International press release

1968 – The Mother of All Demos

I entered Stanford University’s Computer Science (CS) Department in June, 1966, less than a year after its opening, and remained a graduate student there for the next 6 years. The graduate students in CS came from mixed backgrounds, since there had been no definition of CS until around this time.

In the winter of 1968, many of us drove up to San Francisco to attend the Fall Joint Computer Conference at Brooks Hall. And so we were there in the audience when Doug Engelbart took the stage to demonstrate his working model of a system that would “augment human intelligence.”

As I recall the event, Doug was in a chair that had two fixed, flat arms, like the ones you find in schools, except that this chair also could swivel. On the left side he held a mouse, and on the right was a 5-key keyboard. He could type with the 5 keys by pressing one or multiple keys at the same time (this gives you 31 combinations of keystrokes, and some keystrokes changed the “case” to give more options). There was a screen, and the screen contents were also projected onto a large screen that the audience could see.

Steven Levy in his 1994 book, Insanely Great: The Life and Times of Macintosh, the Computer That Changed Everything, describes the event as “a calming voice from Mission Control as the truly final frontier whizzed before their eyes. It was the mother of all demos.”

The impact of this demo was not so great at the time. We thought that he had some interesting ideas, such as “windows” that appeared to be sheets of paper overlapping each other on a “desktop.” He also had pull-down menus and something like hyperlinks. Quite far-out stuff. But what made the demo stand out compared to everything else in computing at the time was the fact that Doug – a SINGLE — USER – was employing the full computing power of a system running down in Menlo Park that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. We didn’t think of computers as “personal” in any sense in those days.

Transition to Xerox PARC

Within a few years, Xerox had founded the Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), and in time, the ideas that Doug had developed made the transition to Xerox PARC and were refined in the Alto personal system for internal use at PARC. (For more on PARC, see Dealers of Lightning by Michael Hiltzik)

Apple Lisa – bringing the Xerox Alto/Star to Apple

In 1979, I started working for Apple Computer as a hardware designer on the Lisa team. We initially were implementing a microprogrammed version of UCSD Pascal, but soon dropped the design to go with the Motorola 68000 CPU chip. About this time, Steve Jobs made his now-famous visit to Xerox PARC and came back very excited about the user interface – windows, pull-down menus, bit-mapped graphics – that had evolved from Doug Engelbart’s work.

The Lisa software team acquired numerous people from Xerox PARC and that led to the second commercial version of Doug Engelbart’s ideas (the first was the Xerox STAR, a $20,000 system). The Lisa (1983) reduced that cost to about $10,000; but it wasn’t until the Macintosh (1984) that Doug’s ideas were found on a truly personal (and affordable) computer.

1996 – Quantum Strategic Teams

Meanwhile, I spent 10 years consulting for a variety of firms in Silicon Valley. One of those was Quantum, a hard disk drive maker. In 1993, I hired into Quantum to build a new department called Systems Engineering.

In 1996, Quantum invited me to join a strategic planning effort that recruited 16 employees – two teams of 8 – to look 10 years ahead and set Quantum’s direction for the future, using a process outlined in Prahalad & Hamel’s book, Competing for the Future. We were encouraged to engage the forward-thinkers of the Bay Area to stimulate our ideas. Remembering Doug Engelbart’s demo, I located Doug and invited him to come to Quantum for a day.

By this time, Doug’s office was lodged in Fremont, in a corner of a building where Logitech made computer mice and other gear. Pierluigi Zappacosta, founder of Logitech, was grateful to Doug for his inventions and offered him free use of this space.

During Doug’s day at Quantum, I learned more about his approach to research. In particular, there were three things that stood out for me:

First, there was what Doug showed as a spiral – the iterative improvement in human capability that comes from improving the tools a person uses. As the tools improve, the person can fashion additional and further-improved tools to keep the spiral growing.

Second, Doug was focused on the individual at work, including the ways in which an individual communicates with another individual. In this context, he was the prototype of the original “user experience designer” – a person who is concerned only with how things appear to the user and what the user can accomplish.

Third, Doug clearly understood and relied on Moore’s Law, the cost trend that brings double the computing power to a constant-cost chip every 1.5 to 2 years. For Doug, this is what was guaranteed to bring – within a few decades from 1968 –sufficient computing resources at reasonable cost into the hands of the individual.

What should we learn from this man’s life?

The lives of the heroes, someone once said, are not to be taken as models, but as lessons. Here are some of the lessons I believe we should learn from Doug’s life.

A. The life of a visionary is often lonely, because he or she can see what is to come long before others can. In Doug’s case, it took 30 years to arrive at the fruition of his ideas. He was fortunate that he lived to see that arrival.

B. Not all visionaries get to run a company and drive it to their vision. Steve Jobs was a rare exception, and even he had real success only on the third try.

C. When you’re inventing things, you have to plan to throw away a lot of prototypes. This is a test of persistence and courage. Doug had these traits.

D. Ultimate success comes from patient work towards a goal clearly seen. The critical components of such work are the patience and the clarity. Few of us maintain the level of clarity that Doug Engelbart achieved, and fewer still have the patience to return again and again to the vision.

We should all feel inspired by Doug’s life: not by his “success” as measured in the commercial world, but by the example he set of steady vision, patiently explained and consistently followed.

Indeed, Doug was most interested in collaboration as the pinnacle of multiplying human intelligence. The “gadgets” were only a means to the end of better interactions.

Thank you for this fascinating story of Doug and his contribution to increased collaboration in teams separated by distance. When I had one precious opportunity to speak with Doug in person he expressed regret that the global collaboration he’d envisioned had not yet manifested. When I told him about working with rooms of 20 people from 6 different countries, and how afterwards they were collaborating virtually – across borders and boundaries of every kind – thanks in part to his pioneering work . . . well, he was visibly moved. I personally feel that global businesses are the perfect laboratory to continue Doug’s “Great Collaboration Experiment”. While governments mainly focus on their own country’s needs, global businesses operate in dozens of countries (UPS has operations in EVERY country!), and they have a strong motivation to work together profitably, and thus sustainably. Doug wanted to be remembered for advancing collaboration, not inventing gadgets, and that’s how I will always remember him.